In 1950s, Chicago's Puerto Rican population was small but growing. Like many immigrant communities, they were pushed into the city's most neglected neighborhoods. Gambling, drugs, and prostitution were rampant. Many were unemployed, under-employed and underpaid. Puerto Ricans had no political representation in the city and almost no organizations to champion their causes. Puerto Ricans faced routine harassment from police and white gangs. In the summer of 1966, tensions boiled over when a white police officer fatally shot 20-year-old Arcelis Cruz, an unarmed Puerto Rican man. The shooting sparked three days of riots and looting.

At that time, the Young Lords were just one of many street gangs in Chicago, formed mainly for self-defense. Composed largely of second-generation Puerto Ricans, they emerged as a response to white gang violence and police neglect. But in the late 1960s, the gang began to change—dramatically.

That shift was led by José “Cha Cha” Jiménez. In and out of jail, Jiménez began reading Martin Luther King Jr. and forged a friendship with Fred Hampton of the Black Panthers. His perspective shifted: beyond rival gangs, he began to see the police, landlords, and city officials as powerful forces that sustained racial and economic injustice. Police harassment wasn't isolated or random; it was systemic. Residents described being treated “like animals,” and many felt that the police presence made their neighborhoods feel more dangerous, not less.

By 1967, Jiménez had transformed the Young Lords from a gang into a political organization: the Young Lords Organization (YLO). Their first act as activists was to broker truces with rival gangs and redirect action toward institutions of repression.

At its peak the organization claimed to have one thousand members. They ranged in age from children of twelve years to men and women in their early thirties. Some members gave up jobs to dedicate themselves fully to organizing, receiving a small per diem for food and essentials.

The organization helped to support itself by selling a monthly newspaper. The newspaper, published in both Spanish and English, printed articles on local, national and international affairs. The Lords envisioned the newspaper as a tool that would help heighten the level of political consciousness within the Latino community. Since the paper was published only once a month, it could not sustain the organization financially, so Lords also sold posters and buttons and solicited donations from philanthropists and local businesses.

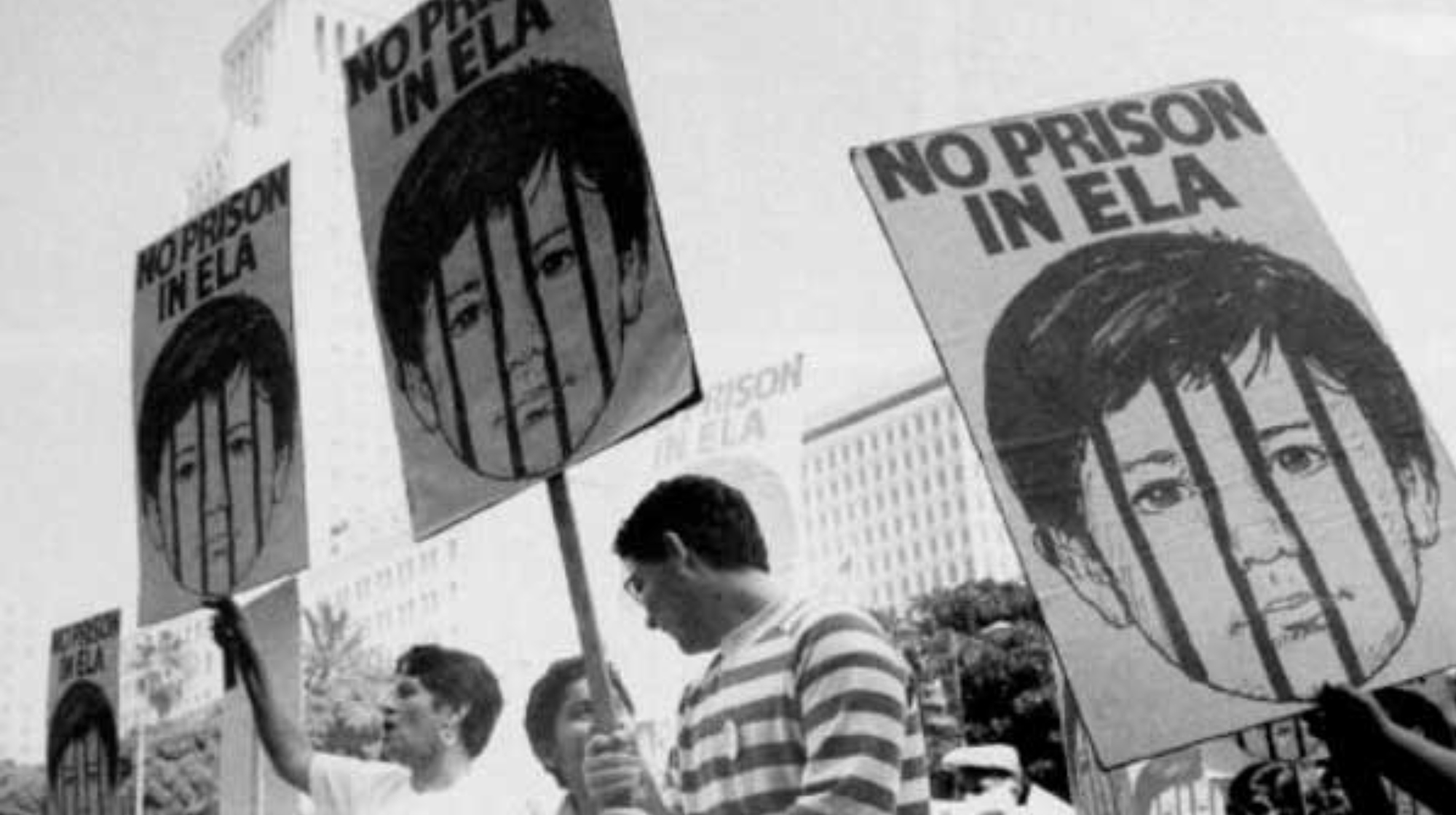

One of their signature tactics was the occupation of institutions to demand community control and resources. For example, in 1969, the Young Lords occupied the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago to publicize the city's attempts to displace Puerto Ricans from the Lincoln Park community and charged that the seminary was complicit in this displacement. Their demands and presence garnered major media coverage, boosted recruitment, and pressured the seminary into committing six hundred thousand dollars to housing initiatives and opening its facilities to the community.

Another tactic was transforming community spaces from within. The Young Lords asked officials at the Armitage Avenue Methodist Church for permission to establish a daycare center. Well, many white residents of Lincoln Park opposed the idea of a daycare center and asked city inspectors for an investigation of the site to determine if it would be in compliance with state regulations. Inspectors found 11 violations and estimated $10,000 in repair costs—an attempt to shut the project down. Undeterred, the Young Lords raised the money and opened the daycare center two months later.

They also ran a free breakfast program for children, neighborhood clean-ups, and clothing drives. At their breakfast sites, they played the Puerto Rican national anthem each morning to help foster cultural pride.

In 1970, Lords opened a free community clinic, staffed with doctors, nursing students, and other healthcare volunteers. A third year medical student at Northwestern University supervised the clinic. The clinic served nearly fifty people every Saturday, with services from prenatal care to eye examinations. At first some residents were reluctant to visit the clinic. They were still leery of the Lords' old gang image and were frightened by what they read in the newspapers. Recognizing their credibility problem, the Young Lords started canvassing door-to-door, asking residents if anyone needed medical care and making arrangements for them to go to the clinic. If the people didn't appear, they were sent a follow-up letter inviting them to visit the clinic. They even made house calls for those with mobility issues.

The Health Clinic became the most successful organizing tool for the Lords.

Of course, mayor Richard Daley viewed the Lords as an obstacle to his urban renewal agenda, which often meant displacing poor residents to make way for gentrification. After declaring a “war on gangs,” Daley's administration used police harassment, frequent arrests, and legal pressure to sap the Lords' resources and discourage new recruits.

By 1971 the group began to struggle, becoming more ideologically strident and unfortunately abandoning many of its community projects.

But the impact of those five years had been large. The Young Lords sparked a cultural and political awakening among Puerto Ricans in Chicago and beyond. Young Lord chapters sprang up across the country and became a vehicle for the political maturation for many second and third generation Puerto Ricans. In Chicago itself, by 1975 three Latinos had been elected to public office. New groups such as the Puerto Rican Cultural Center and the Centro Cultural Segundo Ruiz Belvis, the Westtown Concerned Citizens Coalition and the creation of Puerto Rican Students Unions drew inspiration from the Young Lords.

Just a little coda to the story, the person most credited with transforming Young Lords from a gang into a community organization, Cha Cha Jimenez, died just a few months ago, at age 76.

Much of this content comes from the article in Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, “From Gang-Bangers to Urban Revolutionaries: The Young Lords of Chicago” by Judson Jeffries.

I hope this story gave you some ideas about how to build change. Young Lords were bold and refused to give up on their community, even if their numbers were pretty small.